|

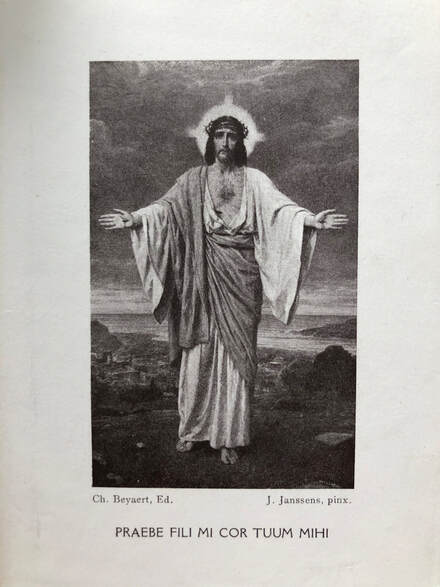

Last year I found a hundred-year-old copy of St. John's Spiritual Canticle in a second hand bookshop. The above image was tucked between the pages. The Latin text reads: 'My son, give Me your heart.'

For those who haven’t yet seen yesterday’s address by UK Health Secretary, the Right Honourable Matthew Hancock, the government is now talking about a plan to roll out ‘immunity passports’ to the UK within the coming months. These passports would only be issued to those who tested positive for antibodies showing that they’d already had the novel coronavirus and were, therefore, immune. They would then, in theory, be able to return to normal life. Attempts to establish a reliable method of testing in this area have, so far, yielded mixed results – but our leaders seem confident that they will be able to procure a test which we can use with confidence. Please, God. Until then, lockdown continues. Many commentators and journalists have already pointed out that how one experiences lockdown is very much a class issue; quarantine is generally a lot less of an ordeal if you live in a spacious, detached home with a nice garden than if you’re in a multiple-occupancy residency or a grotty urban high-rise. If you’re in the latter category, or if for whatever reason you find yourself confined to a single room at this time, know that our hearts go out to you and that you are in our prayers. My hope is that you will find particular comfort and inspiration in the life of the saint who is the subject of today’s blog post: John of the Cross. John was born in 1542 in a small town near Avíla, Old Castile. No stranger to suffering, during his childhood he experienced debilitating poverty and the deaths of both his father and brother. In spite of this he remained devoutly religious, entering the Carmelite order at the age of twenty-one. In 1567, he was ordained as a priest, and it was in that same year that he first met St. Teresa of Avíla, then known simply by her Carmelite name: Teresa of Jesus. Teresa was in the process of reforming the Carmelite order, feeling that it had deviated so much from its roots that it was no longer a place in which souls could adequately seek Christian perfection. Teresa envisaged an order which would live a much simpler, more austere life including long periods of silence and forbidding the wearing of covered shoes. It was from this last principle that the name of the new order, the Discalced (meaning barefoot) Carmelites was derived. John had originally intended to switch to the Carthusian order; however, having shadowed Teresa for some time he decided to join her in her reforms, founding a new monastery for Carmelite friars and changing his name to ‘John of the Cross’. John and Teresa’s reforms caused great tension within the original order. In December 1577, a group of Carmelites who opposed the reforms kidnapped John and took him to the Carmelite monastery in Toledo, where he was jailed in a tiny cell with barely enough room to lie down. The cell had no natural light and the only way John could read his breviary was by standing on the bench and holding it in a small shaft of light from the adjoining room, which came through a hole in the wall. His captors fed him on bread, water and scraps of fish, denying him even the most basic comforts, such as a change of clothing. As if all this weren’t enough, he was taken out of his cell once a week to be publicly flogged. John remained in this place for eight months before he finally managed to escape, meaning he would have spent the coldest (Spain is horrible in February) and hottest months of the year in that tiny cell. One can only imagine the toll that the stifling heat of the Spanish summer and lack of ventilation must have had on his mind and body. Indeed, his imprisonment must have carried an extra sting because it happened at the hands of other people who bore the name of Christ. Yet it was during this period that John produced some of his finest literary work, writing several short poems as well as the greater part of his masterpiece: The Spiritual Canticle, a poetic retelling of the Song of Songs. Mirabai Starr describes the process thus: “It was painful enough for him to wonder if God had given up on him, but the true agony descended when he began to find himself giving up on God. At last, he simply ran out of energy and let himself down into the arms of radical unknowingness—which is where the transmutation of the lead of his agony began to unfold into the gold of mystical poetry. . .” In the years that followed his escape, John expressed a profound gratitude for the months he had spent in prison, which had prepared and purified his soul in such a way that enabled him to receive incredible graces from God. To the outside world, his situation may have seemed hopeless, but it was in the dark confines of this little cell that a radical internal metamorphosis took place, and out of a seeming void that new life would eventually spring. In this way John’s imprisonment can be read as imitating the pattern of Christ’s own death and entombment, without which there can be no rising, no glory: “Most assuredly, I say to you, unless a grain of wheat falls into the ground and dies, it remains alone; but if it dies, it produces much grain” (John 12: 24). I was recently talking to the novice mistress at Stanbrook Abbey, who likened the current situation to one long Easter Saturday: there has been suffering, there has been death, and now the world waits, pregnant with the hope of Resurrection. And what a beautiful hope it is. It might just be that what our planet needs at this particular point in history, even more than a vaccine or an antibody test, is saints. And by embracing and surrendering to our confinement, abandoning ourselves to the good work God wishes to complete in us – it might just be that we find ourselves among them. St. John of the Cross, pray for us! by Lucy Stothard Mirabai Starr, “Exquisite Risk: John of the Cross and the Transformational Power of Captivity,” Emancipation, Oneing Vol. 3 No. 1. (Center for Action and Contemplation: 2015), 59-64.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Lucy Stothard & Fr David & Fr TomasLucy is an Intern at S Giles, Fr Tomas is is our curate, and Fr David is the vicar. We hope to offer some regular words of encouragement during this difficult time. Archives

May 2020

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed